FULL SPECTRUM OPERATIONS IN THE HOMELAND: A “VISION” OF THE FUTURE

Original Post: http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/full-spectrum-operations-in-the-homeland-a-%E2%80%9Cvision%E2%80%9D-of-the-future

The U.S. Army’s Operating Concept 2016-2028 was issued in August 2010 with three goals. First, it aims to portray how future Army forces will conduct operations as part of a joint force to deter conflict, prevail in war, and succeed in a range of contingencies, at home and abroad. Second, the concept describes the employment of Army forces at the tactical and operational levels of war between 2016 and 2028. Third, in broad terms the concept describes how Army headquarters, from theater army to division, organize and use their forces. The concept goes on to describe the major categories of Army operations, identify the capabilities required of Army forces, and guide how force development should be prioritized. The goal of this concept is to establish a common frame of reference for thinking about how the US Army will conduct full spectrum operations in the coming two decades (US Army Training and Doctrine Command, The Army Operating Concept 2016 – 2028, TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-1, dated 19 August 2010, p. iii. Hereafter cited as TD Pam 525-3-1. The Army defines full spectrum operations as the combination of offensive, defensive, and either stability operations overseas or civil support operations on U.S. soil).

A key and understudied aspect of full spectrum operations is how to conduct these operations within American borders. If we face a period of persistent global conflict as outlined in successive National Security Strategy documents, then Army officers are professionally obligated to consider the conduct of operations on U.S. soil. Army capstone and operating concepts must provide guidance concerning how the Army will conduct the range of operations required to defend the republic at home. In this paper, we posit a scenario in which a group of political reactionaries take over a strategically positioned town and have the tacit support of not only local law enforcement but also state government officials, right up to the governor. Under present law, which initially stemmed from bad feelings about Reconstruction, the military’s domestic role is highly circumscribed. In the situation we lay out below, even though the governor refuses to seek federal help to quell the uprising (the usual channel for military assistance), the Constitution allows the president broad leeway in times of insurrection. Citing the precedents of Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War and Dwight D. Eisenhower sending troops to Little Rock in 1957, the president mobilizes the military and the Department of Homeland Security, to regain control of the city. This scenario requires us to consider how domestic intelligence is gathered and shared, the role of local law enforcement (to the extent that it supports the operation), the scope and limits of the Insurrection Act–for example maintaining a military chain of command but in support of the Attorney General as the Department of Justice is the Lead Federal Agency (LFA) under the conditions of the Act–and the roles of the local, national, and international media.

The Scenario (2016)

The Great Recession of the early twenty-first century lasts far longer than anyone anticipated. After a change in control of the White House and Congress in 2012, the governing party cuts off all funding that had been dedicated to boosting the economy or toward relief. The United States economy has flatlined, much like Japan’s in the 1990s, for the better part of a decade. By 2016, the economy shows signs of reawakening, but the middle and lower-middle classes have yet to experience much in the way of job growth or pay raises. Unemployment continues to hover perilously close to double digits, small businesses cannot meet bankers’ terms to borrow money, and taxes on the middle class remain relatively high. A high-profile and vocal minority has directed the public’s fear and frustration at nonwhites and immigrants. After almost ten years of race-baiting and immigrant-bashing by right-wing demagogues, nearly one in five Americans reports being vehemently opposed to immigration, legal or illegal, and even U.S.-born nonwhites have become occasional targets for mobs of angry whites.

In May 2016 an extremist militia motivated by the goals of the “tea party” movement takes over the government of Darlington, South Carolina, occupying City Hall, disbanding the city council, and placing the mayor under house arrest. Activists remove the chief of police and either disarm local police and county sheriff departments or discourage them from interfering. In truth, this is hardly necessary. Many law enforcement officials already are sympathetic to the tea party’s agenda, know many of the people involved, and have made clear they will not challenge the takeover. The militia members are organized and have a relatively well thought-out plan of action.

With Darlington under their control, militia members quickly move beyond the city limits to establish “check points” – in reality, something more like choke points — on major transportation lines. Traffic on I-95, the East Coast’s main north-south artery; I-20; and commercial and passenger rail lines are stopped and searched, allegedly for “illegal aliens.” Citizens who complain are immediately detained. Activists also collect “tolls” from drivers, ostensibly to maintain public schools and various city and county programs, but evidence suggests the money is actually going toward quickly increasing stores of heavy weapons and ammunition. They also take over the town web site and use social media sites to get their message out unrestricted.

When the leaders of the group hold a press conference to announce their goals, they invoke the Declaration of Independence and argue that the current form of the federal government is not deriving its “just powers from the consent of the governed” but is actually “destructive to these ends.” Therefore, they say, the people can alter or abolish the existing government and replace it with another that, in the words of the Declaration, “shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.” While mainstream politicians and citizens react with alarm, the “tea party” insurrectionists in South Carolina enjoy a groundswell of support from other tea party groups, militias, racist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan, anti-immigrant associations such as the Minutemen, and other right-wing groups. At the press conference the masked militia members’ uniforms sport a unit seal with a man wearing a tricorn hat and carrying a musket over the motto “Today’s Minutemen.” When a reporter asked the leaders who are the “red coats” the spokesman answered, “I don’t know who the redcoats are…it could be federal troops.” Experts warn that while these groups heretofore have been considered weak and marginal, the rapid coalescence among them poses a genuine national threat.

The mayor of Darlington calls the governor and his congressman. He cannot act to counter the efforts of the local tea party because he is confined to his home and under guard. The governor, who ran on a platform that professed sympathy with tea party goals, is reluctant to confront the militia directly. He refuses to call out the National Guard. He has the State Police monitor the roadblocks and checkpoints on the interstate and state roads but does not order the authorities to take further action. In public the governor calls for calm and proposes talks with the local tea party to resolve issues. Privately, he sends word through aides asking the federal government to act to restore order. Due to his previous stance and the appearance of being “pro” tea party goals the governor has little political room to maneuver.

The Department of Homeland Security responds to the governor’s request by asking for defense support to civil law enforcement. After the Department of Justice states that the conditions in Darlington and surrounding areas meet the conditions necessary to invoke the Insurrection Act, the President invokes it.

(From Title 10 US Code the President may use the militia or Armed Forces to:

§ 331 – Suppress an insurrection against a State government at the request of the Legislature or, if not in session, the Governor.

§ 332 – Suppress unlawful obstruction or rebellion against the U.S.

§ 333 – Suppress insurrection or domestic violence if it (1) hinders the execution of the laws to the extent that a part or class of citizens are deprived of Constitutional rights and the State is unable or refuses to protect those rights or (2) obstructs the execution of any Federal law or impedes the course of justice under Federal laws.)

By proclamation he calls on the insurrectionists to disperse peacefully within 15 days. There is no violation of the Posse Comitatus Act. The President appoints the Attorney General and the Department of Justice as the lead federal agency to deal with the crisis. The President calls the South Carolina National Guard to federal service. The Joint Staff in Washington, D.C., alerts U.S. Northern Command, the headquarters responsible for the defense of North America, to begin crisis action planning. Northern Command in turn alerts U.S. Army North/Fifth U.S. Army for operations as a Joint Task Force headquarters. Army units at Fort Bragg, N.C.; Fort Stewart, Ga.; and Marines at Camp Lejuene, N.C. go on alert. The full range of media, national and international, is on scene.

“Fix Darlington, but don’t destroy it!”

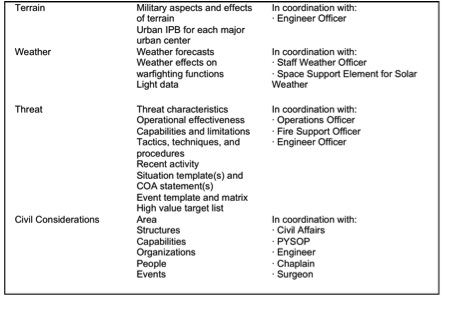

Upon receiving the alert for possible operations in Darlington, the Fifth Army staff begins the military decision making process with mission analysis and intelligence preparation of the battlefield. (Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield is the term applied to the procedures performed by the intelligence staff of all Army unit headquarters in the development of bases of information on the enemy, terrain and weather, critical buildings and facilities in a region and other points. Army units conduct operations on the basis of this information. The term is in Army doctrine and could be problematic when conducted in advance of operations on U.S. soil. The general form of the initial intelligence estimate is in figure 1.) In developing the intelligence estimate military intelligence planners will confront the first constraints on the conduct of full spectrum operations in the United States, as well as constraints on supporting law enforcement. The analytical steps of the Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield, or IPB, must be modified in preparing for and conducting operations in the homeland.

The steps of the IPB process are: define the operational environment/battlespace, describe environmental effects on operations/describe battlespace effects, evaluate the threat/adversary, and determine threat/adversary courses of action. (PSYOP was changed to Military Information Support Operations, MISO, by Secretary of Defense directive in June 2010.)

While preparing terrain and weather data do not pose a major problem to the G-2, gathering data on the threat and under civil considerations for intelligence and operational purposes is problematic to say the least.

Figure 1: The Intelligence Estimate (FM 2-01.3, p. 7, chapter 1)

Executive Order 12333, United States Intelligence Activities, dated 4 December 1981, relates mostly to intelligence gathering outside the continental United States. However, it also outlines in broad terms permissible information-gathering within the United States and on American citizens and permanent resident aliens, categorized as United States persons. (The executive order included in its definition of “United States persons” unincorporated associations mostly comprising American citizens or permanent resident aliens; or a corporation incorporated in the United States, except for a corporation directed and controlled by a foreign government or governments. The basic thrust of the rules and regulations concerning intelligence collection and dissemination are focused on protecting American citizens’ Constitutional rights. These rules and regulations are focused, properly, on support to law enforcement. They do not contain much guidance concerning the conduct of full spectrum operations such as the situation facing the corps. While the best practice as described in FM 3-28 is to retain just enough for situational awareness and force protection the situation facing the corps strains the limits of situational awareness and could place the G2 and commanders at some risk once the dust has settled in the aftermath of an operation within the homeland.) The Fifth Army intelligence analysts will have a great deal of difficulty determining tea party members’ legal status. Because the Defense Department does not collect or store information on American civilians or civilian groups during peacetime, the military will have to rely on local and state law enforcement officials at the start of operations to establish intelligence data-bases and ultimately restore the rule of law in Darlington.

Using all intelligence disciplines from human intelligence to signals intelligence, the Fifth Army G2 and his staff section will collect as much information as they need to accomplish the mission. Once the rule of law is restored the Fifth Army G2 must ensure that it destroys information gathered during the operation within 90 days unless the law or the Secretary of Defense requires the Fifth Army to keep it for use in legal cases (Field Manual 3-28, Civil Support Operations, pp. 7-13. The FM cites Department of Defense Directive, DODD, 5200.27). Because of the legal constraints on the military’s involvement in domestic affairs and the sympathies of local law enforcement, developing the initial intelligence, a continuing estimate, and potential adversary courses of action (what the insurrectionists holding Darlington and surrounding areas might do in response to Army operations) will be difficult. (The closest guidance on handling information collected in the course of civil disturbance operations is in Department of Defense Directive 5200.27 and Department of Defense Directive 5240.1R. These directives state: “Operations Related to Civil Disturbance. The Attorney General is the chief civilian officer in charge of coordinating all federal government activities relating to civil disturbances. Upon specific prior authorization of the Secretary of Defense or his designee, information may be acquired that is essential to meet operational requirements flowing from the mission as to DOD to assist civil authorities in dealing with civil disturbances. Such authorization will only be granted when there is a distinct threat of a civil disturbance exceeding the law enforcement capabilities of State and local authorities.”)

Fifth Army terrain analysts continue using open sources ranging from Google maps to Map-quest. Federal legal restrictions on assembling databases remain in effect and even incidental imagery, aerial photos gathered in the conduct of previously conducted training missions, cannot be used. Surveillance of the tea party roadblocks and checkpoints around Darlington proceeds carefully. Developing legal data-bases is one effort, but support for local law enforcement is hindered because of problems in determining how to share this information and with whom.

Despite these problems, receiving support from local law enforcement is critical to restoring the rule of law in Darlington. City police officers, county sheriff deputies and state troopers can contribute valuable local knowledge of personalities, customs and terrain beyond what can be found in data-bases and observation. Liaison officers and non-commissioned officers, with appropriate communications equipment must be exchanged. Given the suspicion that local police are sympathetic to the tea party members’ goals special consideration to operational security must be incorporated into planning. Informally communicating to the insurrectionists the determination of federal forces to restore local government can materially improve the likelihood of success. However, informants sympathetic to the tea party could easily compromise the element of surprise. The fact that a federal court must authorize wire taps in every instance also complicate the monitoring of communications into and out of Darlington. Operations in Darlington specifically and in the homeland generally must also take into account the possibility of increased violence and the range of responses to violence.

All federal military forces involved in civil support must follow the standing rules for the use of force (SRUF) specified by the Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff. Much like the rules of force issued to the 7th Infantry Division during operations in Los Angeles in 1992 the underlying principle involves a continuum of force, a graduated level of response determined by civilians’ behavior. Fifth Army must assume that every incident of gunfire will be investigated. (Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction, CJCSI, 3121.01B, Standing Rules of Engagement/Standing Rules for the Use of Force for US Forces. There are many similarities between rules for the use of force and rules of engagement, the right of self-defense for example. The fundamental difference is rules of engagement are by nature permissive measures intended to allow the maximum use of destructive combat power appropriate for the mission. Rules for the use of force are restrictive measures intended to allow only the minimum force necessary to accomplish the mission.) All units involved must also realize that operations will be conducted under the close scrutiny of the media.

Operating under media scrutiny is not a new phenomenon for the U.S. military. What is new and newsworthy about this operation is that it is taking place in the continental United States. Commanders and staffs must think about the effect of this attention and be alert when considering how to use the media. The media will broadcast the President’s proclamation and cover military preparations for operations in Darlington. Their reports will be as available to tea party leaders in Darlington as they are to a family watching the evening news in San Francisco. Coupled with a gradual build-up of federal forces in the local area, all covered by the media, the effect of this pressure will compound over time and quite possibly cause doubt about the correctness of the events in Darlington in the minds of its’ citizens and the insurrectionists who control the town. The Joint Task Force commander, staff and subordinate units must operate as transparently as possible, while still giving due consideration to operational security. Commanders must manage these issues even as they increase pressure on the insurrectionists.

The design of this plan to restore the rule of law to Darlington will include information/influence operations designed to present a picture of the federal response and the inevitable defeat of the insurrection. The concept of the joint plan includes a phased deployment of selected forces into the area beginning with reconnaissance and military intelligence units. Once the Fifth Army commander determines he has a complete picture of activity within the town and especially of the insurrectionists’ patterns of behavior, deployment of combat, combat support and combat service support forces will begin from Forts Bragg and Stewart, and Camp Lejuene. Commanders will need to consider how the insurrectionists will respond. Soldiers and Marines involved in this operation, and especially their families will be subject to electronic mail, Facebook messages, Twitters, and all manner of information and source of pressure. Given that Soldiers and Marines stationed at Forts Bragg and Stewart as well as Camp Lejuene live relatively nearby and that many come from this region, chances are they will know someone who lives in or near Darlington. Countering Al Qaeda web-based propaganda is one thing, countering domestic information bombardments is another effort entirely.

The design and execution of operations to restore the rule of law in Darlington will be complicated. The Fifth Army will retain a military chain of command for regular Army and Marine Corps units along with the federalized South Carolina National Guard, but will be in support of the Department of Justice as the Lead Federal Agency, LFA. The Attorney General may designate a Senior Civilian Representative of the Attorney General (SCRAG) to coordinate the efforts of all Federal agencies. The SCRAG has the authority to assign missions to federal military forces. The Attorney General may also appoint a Senior Federal Law Enforcement Officer (SFLEO) to coordinate all Federal law enforcement activities.

The pace of the operation needs to be deliberate and controlled. Combat units will conduct overt Show of Force operations to remind the insurrectionists they are now facing professional military forces, with all the training and equipment that implies. Army and Marine units will remove road blocks and check points both overtly and covertly with minimum essential force to ratchet up pressure continually on insurrectionist leadership. Representatives of state and local government as well as federalized South Carolina National Guard units will care for residents choosing to flee Darlington. A focus on the humanitarian aspect of the effort will be politically more palatable for the state and local officials. Federal forces continue to tighten the noose as troops seize and secure power and water stations, radio and TV stations, and hospitals. The final phase of the operation, restoring order and returning properly elected officials to their offices, will be the most sensitive.

Movements must be planned and executed more carefully than the operations that established the conditions for handover. At this point military operations will be on the downturn but the need for more politically aware military advice will not. War, and the use of federal military force on U.S. soil, remains an extension of policy by other means. Given the invocation of the Insurrection Act, the federal government must defeat the insurrection, preferably with minimum force. Insurrectionists and their sympathizers must have no doubt that an uprising against the Constitution will be defeated. Dealing with the leaders of the insurrection can be left to the proper authorities, but drawing from America history, military advice would suggest an amnesty for individual members of the militia and prosecution for leaders of the movement who broke the law. This fictional scenario leads not to conclusions but points to ponder when considering 21st century full spectrum operations in the continental United States.

The Insurrection Act does not need to be changed for the 21st century. Because it is broadly written, the law allows the flexibility needed to address a range of threats to the Republic.

What we must consider in the design of homeland defense or security exercises is translating the Act into action. The Army Operating Concept describes Homeland Defense as the protection of “U.S. sovereignty, territory, domestic population, and critical defense infrastructure against external threats and aggression, or other threats as directed by the president” (TD Pam 525-3-1, p. 27. Emphasis added.) Neither the operating concept nor recently published Army doctrine, FM 3-28 Civil Support Operations, goes into detail when considering the range of “other threats.” While invoking the Insurrection Act must be a last resort, once it is put into play Americans will expect the military to execute without pause and as professionally as if it were acting overseas. The Army cannot disappoint the American people, especially in such a moment. While real problems and real difficulties of such operations may not be perceived until the point of execution preparation will afford the Army the ability to not be too badly wrong at the outset.

Being not too badly wrong at the outset requires focused military education on the nuances of operations in the homeland. Army doctrine defines full spectrum operations as a mix of offense, defense and either stability or civil support operations. Curriculum development is a true zero sum game; when a subject is added another must be removed. Given the array of threats and adversaries; from “commando-style” raids such as Mumbai, the changing face of militias in the United States, rising unrest in Mexico, and the tendency to the extreme in American politics the subject of how American armed forces will conduct security and defense operations within the continental U.S. must be addressed in the curricula of our Staff and War Colleges. (The Kansas City Star, 12 September 2010, “The New Militia.” The front page story concerns the changing tactics of militia movements and how militias now focus on community service and away from violence against the government. Law enforcement agencies feel this is camouflage for true intentions. The story covered armed paramilitary militias in Missouri and Kansas.)

The Army must address the how to of intelligence/information gathering and sharing, liaison with local law enforcement and conduct of Information Operations in focused exercises, such as UNIFIED QUEST, given a wider range of invited participants. The real question of how to educate the Army on full spectrum operations under homeland security and defense conditions must be a part of an overall review of professional military education for the 21st century. We cannot discount the agility of an external threat, the evolution of Al Qaeda for example, and its ability to take advantage of a “Darlington event” within U.S. borders. How would we respond to this type of action? What if border violence from Mexico crosses into the United States? The pressure for action will be enormous and the expectation of professional, disciplined military action will be equally so given the faith the American people have in their armed forces. The simple fact is that while the Department of Justice is the Lead Federal Agency in these operations the public face of the operation will be uniformed American Soldiers. On a TV camera a civilian is a civilian but here is no mistaking the mottled battle dress of a Soldier with the U.S. flag on his or her right sleeve.

The table of organization and equipment of Fifth U.S. Army/Army North must be scrutinized. The range of liaison parties that must be exchanged in the conduct of operations on American soil is extensive. Coordination with federal, state and local civil law enforcement and security agencies is a vital element in concluding homeland operations successfully. The liaison parties cannot be ad hoc or last minute additions to the headquarters. At a minimum such parties must routinely exercise with the headquarters.

In 1933 then Colonel George Marshall criticized the education that the Army Command and General Staff College provided as inadequate to “the chaotic state of affairs in the first few months of a campaign with a major power” (From a 1933 letter from COL GC Marshall to MG Stewart Heintzelman, cited in a report on the US Army Command and General Staff College conducted in 1982 by MG Guy Meloy. The report is held in the Special Collections section of the Combined Arms Research Library, Fort Leavenworth, KS.) We must continue on the path of ensuring the avoidance of the “chaotic state of affairs” in the opening moments of future campaigns, defending the nation from within and without. As Dr. Sebastian L. v. Gorka wrote in Joint Forces Quarterly (p. 33), “No concepts are immune to critique and reappraisal when it comes to securing the homeland.”

About the Author(s)

Kevin Benson, Ph.D., Colonel, U.S. Army, Retired, is currently a seminar leader at the University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He holds a B.S. from the United States Military Academy, an M.S. from The Catholic University of America, an MMAS from the School of Advanced Military Studies and a Ph.D. from the University of Kansas. During his career, COL Benson served with the 5th Infantry Division, the 1st Armored Division, the 1st Cavalry Division, the 2nd Cavalry Regiment, XVIII Airborne Corps and Third U.S. Army. He also served as the Director, School of Advanced Military Studies. These are his own opinions and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army or Department of Defense.

Jennifer Weber is an Associate Professor of History (Ph.D. Princeton, 2003) at the University of Kansas. Jennifer Weber specializes in the Civil War, especially the seams where political, social, and military history meet. She has active interests as well in Abraham Lincoln, the 19th century U.S., war and society, and the American presidency. Her first book, Copperheads (Oxford University Press, 2006), about the antiwar movement in the Civil War North, was widely reviewed and has become a highly regarded study of Civil War politics and society. Professor Weber is committed to reaching out to the general public and to young people in her work. Summer’s Bloodiest Days (National Geographic), is a children’s book about the Battle of Gettysburg and its aftermath. The National Council for Social Studies in 2011 named Bloodiest Days a Notable Social Studies Trade Book for Young People. Dr. Weber is very active in the field of Lincoln studies. She has spoken extensively around the country on Lincoln, politics, and other aspects of the Civil War.