GENES

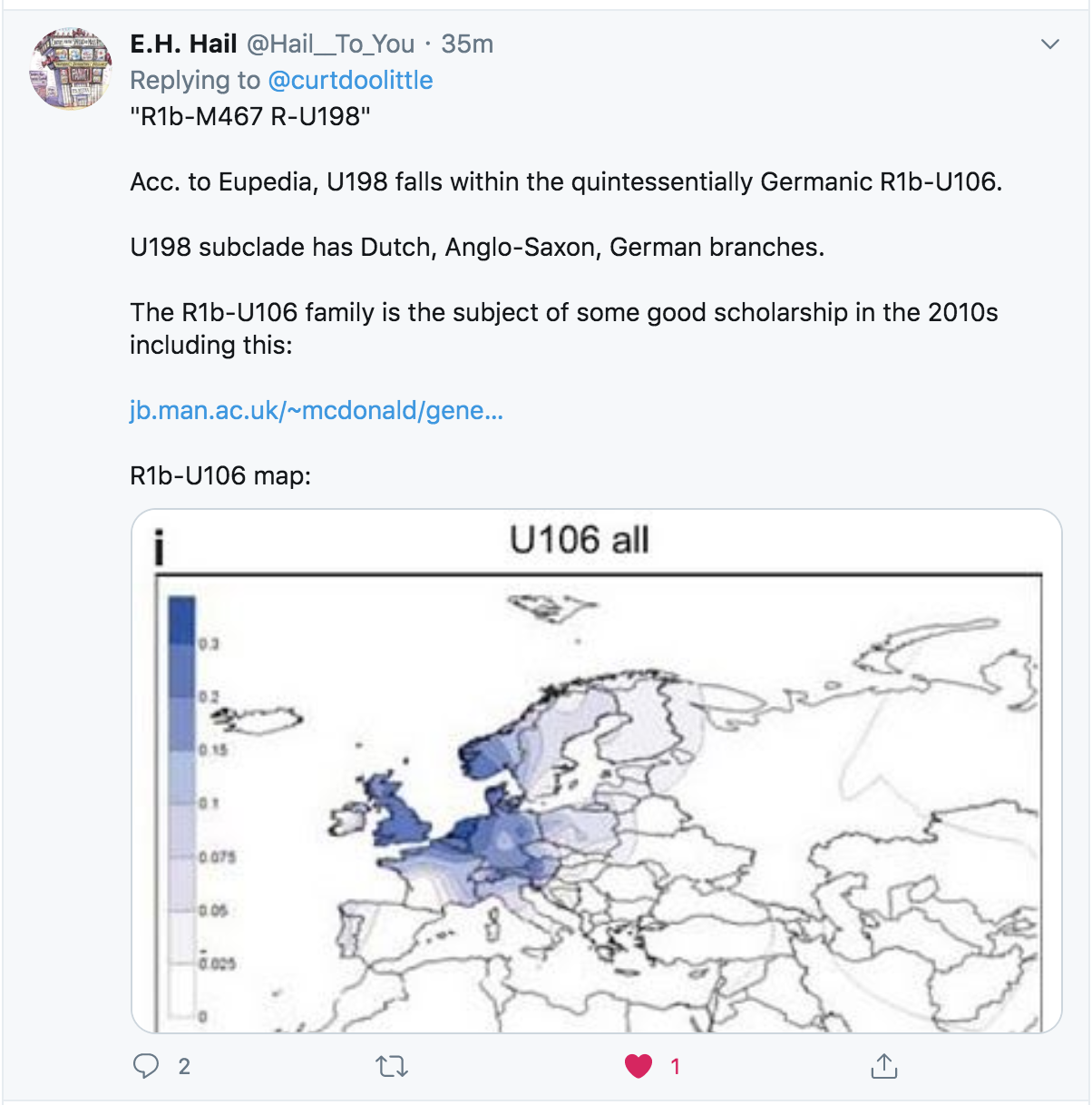

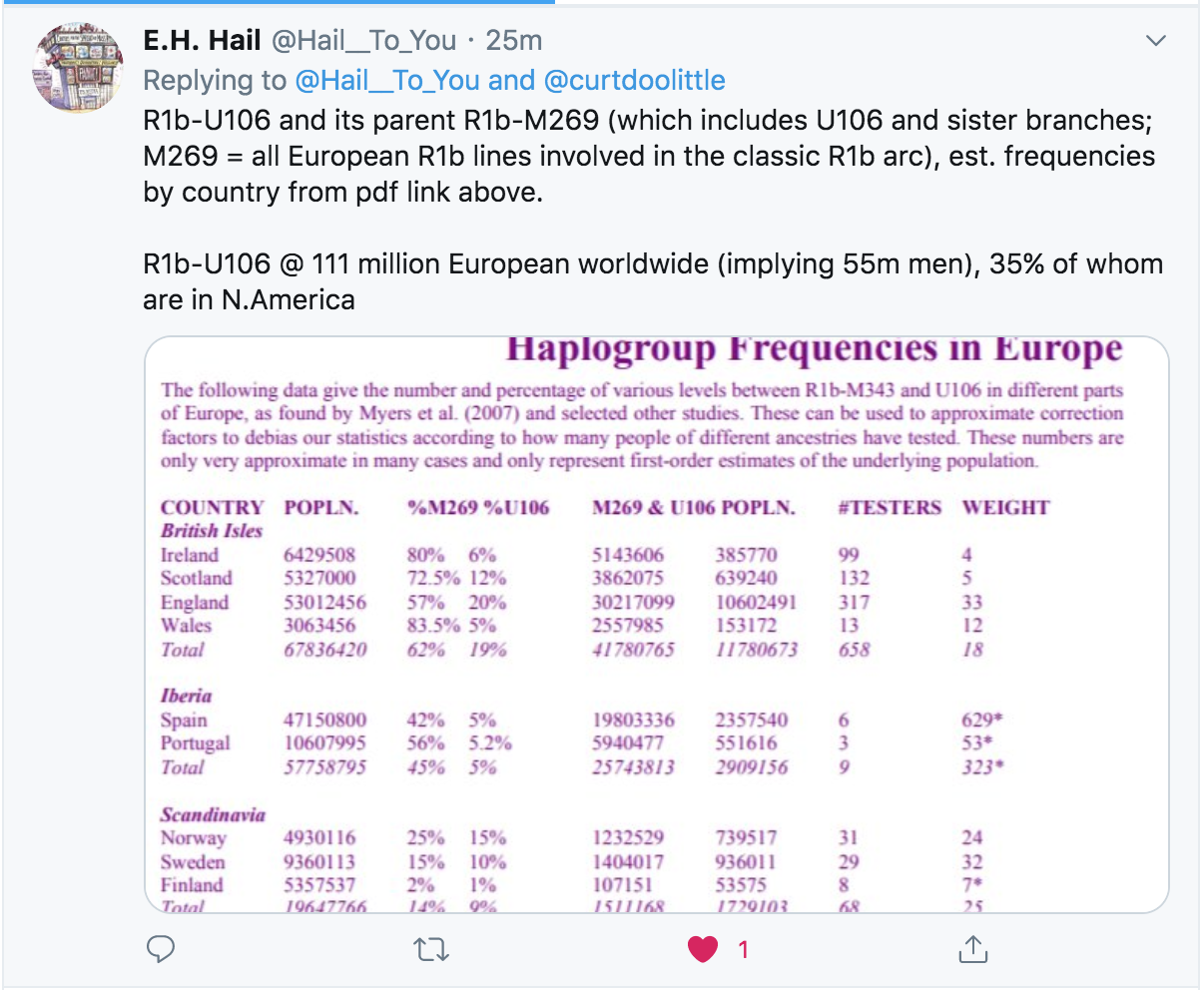

R1b1a2a1a1c2a R1b-M467 R-U198 U198 S29 rs17222279S29

“gs114 > gs252 is a point mutation at position 14727619 on the Y-chromosome in which a “G” has changed to an “A”.”

Doolittle Name

~ Doolittle/Dollittle/Doolette/de Little of Kidderminster. R1b, U106+ > U198+

13092 Doolette Ireland R-M269

13093 de Little England R-U198 <—

14581 Dollittle England R-M269

18645 Doolette Unknown R-M269

–“In 1648, he commanded a troop of five or six Frenchmen along with Algonquins and Hurons to hunt down the Iroquois. On 11 January 1648, Montmagny sent him to the Hurons to invite them to the fur-trade. He went up with two Huron Christians and returned with a group of Hurons who had won a memorable victory over the Mohawks near Trois-Rivières.”–

(My family, on both sides seems to just revel in soldiery – but the canadian french clearly feel ‘defeated’ by the english with their retreat across the border to the states.)

NORMANDY

1040 – Radulfi De Dolieta was born in 1040 at Norman Province, Dolieta, France. Radulfi died at England or Normandy, France.

1066 – Radulphus de Dolieta first Doolittle to come to England from Normandy.

KIDDERMINSTER

Rumor is they went to scotland, but poor land.

Next evidence allotment of land from the king, kidderminster.

Kidderminster is described as “uncommonly devoid of visual pleasure and architectural interest.”

The land around Kidderminster may have been first populated by the Husmerae, an Anglo-Saxon tribe first mentioned in the Ismere Diploma, a document in which Ethelbald of Mercia granted a “parcel of land of ten hides” to Cyneberht.[2] This developed as the settlement of Stour-in-Usmere, which was later the subject of a territorial dispute settled by Offa of Mercia in 781, when he restored certain rights to Bishop Heathored.[3] This allowed for the founding of a monastery or minstre in the area.

The earliest written form of the name Kidderminster (Chedeminstre) was first documented in the Domesday Book of 1086. It was a large manor held by William I, with 16 outlying settlements (Bristitune, Fastochesfeld, Franche, Habberley, Hurcott, Mitton, Oldington, Ribbesford, Sudwale, Sutton, Teulesberge, Trimpley, Wannerton and Wribbenhall). Various spellings were in use – Kedeleministre or Kideministre (in the 12th and 13th centuries), Kidereministre (13th–15th centuries) – until the name of the town was settled as Kidderminster by the 16th century.[3] Between 1156 and 1162 Henry II granted the manor to his steward, Manasser Biset. By six decades later, the settlement grew and a fair (1228) and later a market (1240) were established there.[3] In a visit to the town sometime around 1540, King’s Antiquary John Leland noted that Kidderminster “standeth most by clothing”.[3] King Charles I granted the Borough of Kidderminster a Charter in 1636.[3] the original charter can be viewed at Kidderminster Town Hall

UK – THOMAS DOOLITTLE

after Unknown artist, line engraving, mid 18th century

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Doolittle

after Unknown artist, line engraving, mid 18th century

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Doolittle

Doolittle was the third son of Anthony Doolittle, a glover (and Sergeant), and was born at Kidderminster in 1632 or the latter half of 1631. While at the grammar school of his native town he heard Richard Baxter preach as lecturer (appointed 5 April 1641) the sermons later published as ‘The Saint’s Everlasting Rest’ (1653). These discourses produced a conversion. Placed with a country attorney, he objected to copying writings on Sunday, and went home determined not to follow the law. Baxter encouraged him to enter the ministry.

He was admitted as a sizar at Pembroke Hall, Cambridge, on 7 June 1649, then aged 17. His tutor was William Moses, later ejected from the mastership of Pembroke. Doolittle graduated M.A. at Cambridge. Leaving the university for London he became popular as a preacher, and in preference to other candidates was chosen (1653) as their pastor by the parishioners of St. Alphage, London Wall. The living is described as sequestered in William Rastrick’s list as quoted by Samuel Palmer, but James Halsey, D.D., the deprived rector, had been dead twelve or thirteen years. Doolittle received presbyterian ordination.

On the passing of the Uniformity Act 1662 he thought it his duty to be a nonconformist, though he was poor. He moved to Moorfields and opened a boarding-school, which succeeded. He took a larger house in Bunhill Fields, where he was assisted by Thomas Vincent, ejected from St. Mary Magdalene, Milk Street.

Ejected minister

In the plague year of 1665 Doolittle and his pupils moved to Woodford Bridge, near Chigwell, close to Epping Forest, Vincent remaining behind. Returning to London in 1666, Doolittle was one of the nonconformist ministers who, in defiance of the law, erected preaching-places when churches were lying in ruins after the Great Fire. His first meeting-house (probably a wooden structure) was in Bunhill Fields, and here he was undisturbed. But when he transferred his congregation to a large and substantial building which he had erected in Mugwell (now Monkwell) Street, the authorities set the law in motion against him.

The Lord Mayor tried to persuade him to desist from preaching; he declined. On the following Saturday about midnight his door was broken open by a force sent to arrest him. He escaped over a wall, and intended to preach next day. From this he was dissuaded by his friends, one of whom (Thomas Sare, ejected from Rudford, Gloucestershire) took his place in the pulpit. The sermon was interrupted by the appearance of a body of troops. As the preacher stood his ground the officer told his men to fire.’ ‘Shoot, if you please,’ was the reply. There was uproar, but no arrests were made. The meeting-house, however, was taken possession of in the name of the king, and for some time was used as a Lord Mayor’s chapel.

On the indulgence of 15 March 1672 Doolittle took out a licence for his meeting-house. Doolittle owned the premises, but he now resided in Islington, where his school had developed into an academy for ‘university learning.’ When Charles II (8 March 1673) broke the seal of his declaration of indulgence, thus invalidating the licences granted under it, Doolittle conducted his academy with great caution at Wimbledon. At Wimbledon he had a narrow escape from arrest. He returned to Islington before 1680, but in 1683 was again dislodged. He moved to Battersea (where his goods were seized), and then to Clapham. These migrations destroyed his academy, where his pupils had included Matthew Henry, Samuel Bury, Thomas Emlyn, and Edmund Calamy. Two of his students, John Kerr, M.D., and Thomas Rowe, achieved distinction as nonconformist tutors. The academy was at an end in 1687, when Doolittle lived at St. John’s Court, Clerkenwell, and had Calamy a second time under his care for some months as a boarder. Until the death of his wife he still continued to receive students for the ministry, but apparently not more than one at a time. His last pupil was Nathaniel Humphreys.

After 1689

The Toleration Act of 1689 left Doolittle free to resume his services at Mugwell Street, preaching twice every Sunday and lecturing on Wednesdays. Thomas Vincent, his assistant, had died in 1678; later he had as assistants his pupil, John Mottershead (moved to Ratcliff Cross), his son, Samuel Doolittle (moved to Reading), and Daniel Wilcox, who succeeded him.

His Body of Divinity was an expansion of the Westminster Assembly’s shorter catechism. His private covenant of personal religion (18 November 1693) occupies six closely printed folio pages. He had long suffered from the stone and other infirmities, but his last illness was brief. He preached and catechised on Sunday, 18 May, took to his bed in the latter part of the week, lay for two days unconscious, and died on 24 May 1707. He was the last survivor of the London ejected clergy.

WORKS

Doolittle’s twenty publications are enumerated at the end of the Memoirs (1723), probably by Jeremiah Smith. They consist of sermons and devotional treatises, including:

- ‘Sermon on Assurance in the Morning Exercise at Cripplegate,’ 1661;

- ‘A Treatise concerning the Lord’s Supper,’ 1665 (portrait by R. White), and ‘A Call to Delaying Sinners,’ 1683, which both went through many editions.

His last work published in his lifetime was:

- ‘The Saint’s Convoy to, and Mansions in Heaven,’ 1698.

Posthumous was*

- ‘A Complete Body of Practical Divinity,’ &c. 1723. The editors say this volume was the product of his Wednesday catechetical lectures; the list of subscribers includes Anglican clergymen.

The Works of Thomas Doolittle (1630-1707) available in old English:

1. Sermon on Assurance in the Morning Exercise at Cripplegate

2. A Call to Delaying Sinners

3. The Saint’s Convoy to, and Mansions in Heaven

4. A Complete Body of Practical Divinity

5. Captives Bound in Chains Made Free by Christ Their Surety

6. The Swearer Silenced.

7. Treatise on the Lords Supper.

8. Love to Christ Necessary to Escape the Curse at His Coming.

9. How May the Duty of Daily Family Prayer be best managed.

10. Rebukes for Sin By the Flames of Hell.

11. A plain method of catechizing with a prefatory catechism.

12. Popery is a Novelty.

USA – ABRAHAM

Abraham was born in either 1619 or 1620 a descendant of Reverend Thomas Doolittle (Unlikely. Brother? Cousin?). Abraham married Joane Allen (or “Alling”) and soon afterwards set out for New England. Records indicate Abraham’s presence in Boston in 1640, but he like many others, heard good reports of the fertile lands in what would become Connecticut. Sometime before 1642 the couple arrived in New Haven and built a home. (Note: Although I use the evolved surname of “Doolittle”, Abraham actually used “Dowlittell” as noted in early colonial records.)

Abraham quickly established himself as a well-respected citizen. In 1644, although he was perhaps just twenty-five years old, he was appointed the chief executive officer of the colony. Not only did Abraham deal with issues of concern to his fellow colonists (land, trade, public defense), he also had dealings with the Indians. His participation in New Haven civic affairs was notable as well – according to one historian when an individual of that day was prominent in public affairs it was guaranteed that he was of the highest moral character and an asset to his community.

His wife Jane died and in 1663 he married Abigail Moss, the daughter of John Moss. He and John Moss would later participate in the founding of Wallingford, Connecticut. It is believed that Abraham was the first white man to explore the land beyond the Quinnipac River. Wallingford was incorporate as a town on May 12, 1670.

Again, Abraham plunged into the civic affairs of his town, appointed to almost every position available in the town over the next twenty years until his death in 1690 – including treasurer, surveyor of highways and selectman. In 1673 he was appointed sergeant of the “first traine band” and thereafter bore that title. On February 15, 1675 he was appointed to a committee which would found the town’s first Congregational church.

Records indicate that Abraham served his community continuously until just before his death on August 11, 1690. His grave stone is still standing and quite interesting – a stone about four inches thick and perhaps a foot high and wide, which has his initials, age and date of death etched on it.